What is Gramme Positive and Gramme Negative?

There are many reasons why it’s important to be able to tell the difference between bacterial species, such as finding the species that gives a cheese its unique flavour or diagnosing an illness. Molecular methods like PCR, quantitative PCR, genome sequencing, and mass spectrometry can be used to tell the difference between bacterial species and even types. But there are changes in the way bacteria look that can be used to tell them apart, even if you don’t get into the molecular details. This includes things like their shape (bacilli vs. cocci, for example), how well they grow in certain nutrients, and whether they like places with a lot or little air. Bacterial species may be put into broad groups based on the trait being studied, but when all of this information is put together, it can greatly reduce the number of possible names. One good way to group bacteria is by their cell walls, which show whether they are Gramme positive or Gramme negative.

What is gramme positive and gramme negative?

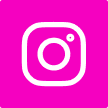

Because Gram-positive bacteria have a single thick peptidoglycan cell wall around them, they are called monoderms. Gramme negative bacteria have a peptidoglycan cell wall that is much thinner. They also have an outer layer with lipopolysaccharides that surrounds the cell, which is why they are called diderms.

| Gram positive bacteria | Gram negative bacteria |

| Distinctive purple appearance after gram staining | Pale reddish color after gram staining |

| Bacteria include all staphylococci, all streptococci and some listeria species | Bacteria include enterobacter species, salmonella species and pseudomonas species |

| Thick peptidoglycan layer | Thin peptidoglycan layer |

| No outer lipid membrane | Outer lipid membrane present |

| No O-specific side chains present | O-specific side chains present |

| Teichoic and lipoteichoic acids present | Teichoic and lipoteichoic acids not present |

How Gramme positive and Gramme negative bacteria are made is different.

The following picture shows how the structures of Gramme positive and Gramme negative bacteria are different. The two main things that make Gramme positive and Gramme negative species visible differently are the thickness of the peptidoglycan layer and whether or not the outer lipid membrane is present. This is because the structure of the cell wall changes how well the crystal violet stain stays on the cell during the Gramme staining process. This stain can then be seen under a light microscope.

Gram-positive bacteria don’t have an outer lipid layer, so they are called monoderms when talking about their structure instead of how they stain. Gramme negative bacteria have an outer lipid layer, which is why they are called diderms when talking about their structure.

Hans Christian Gramme, a Danish bacteriologist, came up with the Gramme colouring method in 1884.1 Even though a Gramme stain won’t tell you exactly what species you are looking at, it can be a quick way to get rid of a lot of possible options and figure out which ones need more testing.

If the mark is Gramme positive or Gramme negative,

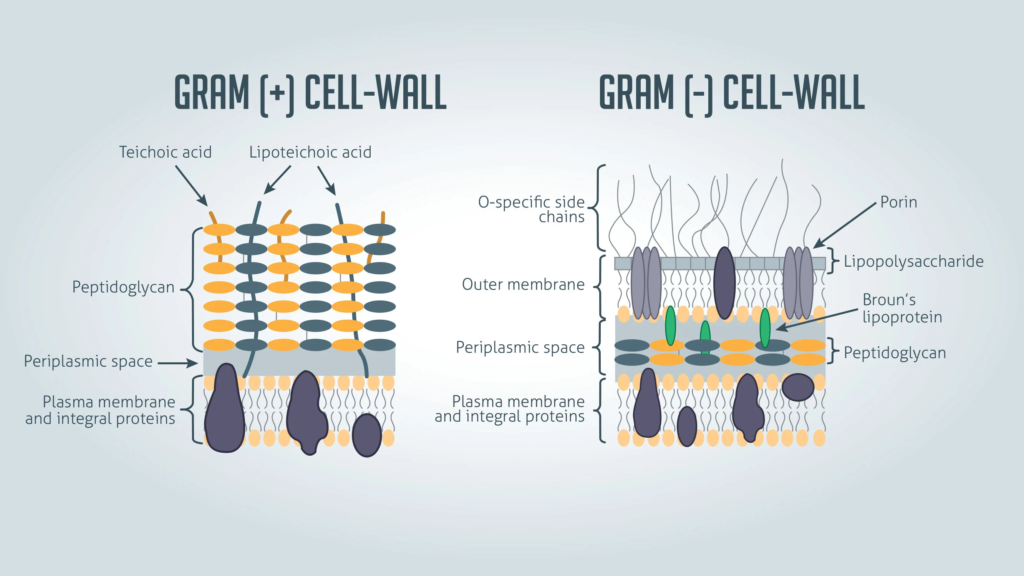

The colour of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria at each step of the gramme staining process

How to do a Gramme stain: getting a sample ready

- Write the name of your subject on a clean glass microscope slide. Make sure you use a pencil because the chemicals used in the colouring process take away a lot of the ink.

- If your slide is going to be made from a liquid bacterial culture:

Using a clean loop, put a small amount of drop culture on the slide. In a rolling motion, spread the droplet out over an area that is about 1 cm in diameter. In cases where the culture is very thick, you might need to dilute it first so that you can see individual bacterial cells after staining.

If the material comes from a bacterial plate, do the following:

Put a loop of colony material back into clean phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and then do the same steps as for a liquid culture.

- Run the smeared slide through a flame two or three times after the smudge has dried naturally.

This kills the germs in the smear and sticks the sample to the slide. Be careful not to heat the sample too much, though, because that can change the shape of the cells.

How to do a Gramme stain: staining a subject with Gramme

- Pour crystal violet over the smudge slowly and let it sit for one minute. Lean the slide back a little and rinse it softly with tap water or distilled water.

Crystal violet is a dye that dissolves in water and gets into the peptidoglycan layer of the cell wall of bacteria.

- Pour Gram’s iodine over the spot slowly and let it sit for one minute. Lean the slide back a little and rinse it softly with tap water or distilled water. The smear will now look purple.

It is mixed with Gram’s iodine solution, which is made up of iodine and potassium iodide, to make a complex with the crystal violet, which is much bigger and doesn’t dissolve in water.

- Use acetone or 95% ethyl alcohol to remove the colour from the smear. Drop by drop, tilt the slide a little, and add the alcohol until it runs almost clear (5 to 10 seconds). Right away, rinse with water to keep from losing too much colour.

The decolorizer dries out the peptidoglycan layer, which makes it smaller and tighter. When it comes to Gramme positive bacteria, the thick peptidoglycan layer stops the big crystal violet-iodine complexes from getting through. This makes the cells purple. In Gramme negative bacteria, on the other hand, the colour is lost because the outer membrane breaks down and the thin peptidoglycan layer can’t hold on to the crystal violet-iodine complexes.

- Flood the area slowly with safranin counterstain and let it sit for 45 seconds. Lean the slide back a little and rinse it softly with tap water or distilled water.

Safranin doesn’t mix well with water and leaves a light red stain on bacterial cells. This makes it possible to see Gramme negative cells without getting in the way of seeing the purple stain on Gramme positive cells.

- Dry the slide on filter paper, and then use a light microscope to look at the spot while it is submerged in oil.

The colour of Gramme positive vs. Gramme negative

Gram-positive germs

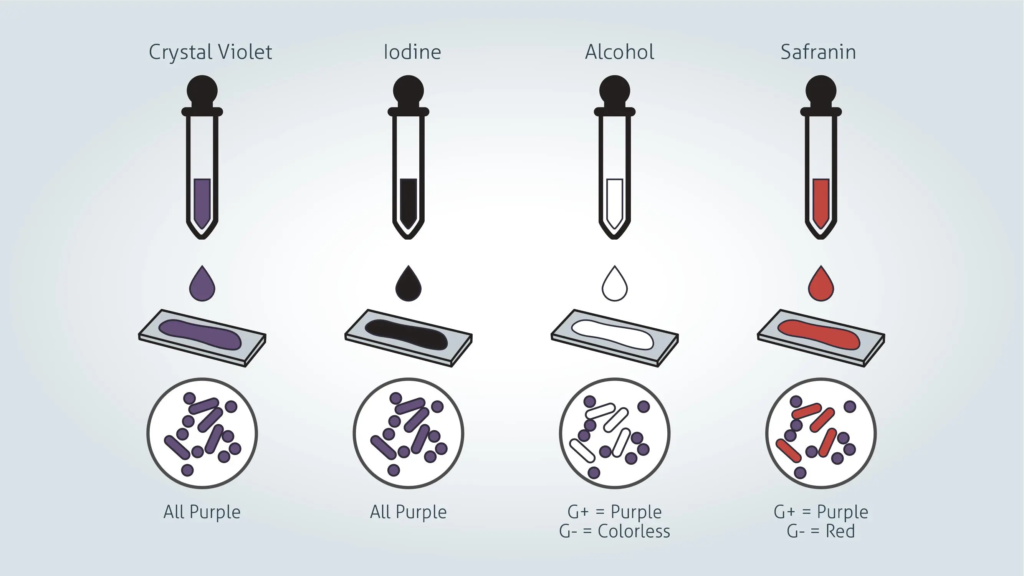

When looked at through a light microscope after Gramme spotting, Gramme positive bacteria have a unique purple colour. There is a thick layer of peptidoglycan in the cell wall that keeps the purple crystal violet stain in place. All staphylococci, all streptococci, and some types of listeria are examples of Gramme positive bacteria.

All staphylococci, all streptococci, and some types of listeria are examples of Gramme positive bacteria.Thanks to Technology Networks

Bacteria with Gramme negative

When looked at through a light microscope after Gramme staining, Gramme negative bacteria have a light reddish colour. They are coloured only by the safranin counterstain because the structure of their cell wall can’t hold the crystal violet stain. Enterobacter species [June 6, 2022], salmonella species, and pseudomonas species are all types of Gramme negative bacteria.

You can’t trust Gramme staining to show how different types of germs are related to each other. It is thought that the single membrane of Gramme positive species is the original state. The second membrane on Gramme negative bacteria was thought to have only evolved once in the past. This meant that all Gramme negative species were more closely related to each other than to Gramme positive species. But genetic testing has since shown that this isn’t true. Instead, it’s likely that it has evolved more than once in different lines, which is called convergent evolution.